Johannes F. Linn

Johannes F. Linn is a nonresident Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution. A former Vice President at the World Bank, Linn has worked in recent years on issues of global governance reform and strengthening multilateral institutions.

Abstract

The international community risks falling substantially short in its efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Paris Agreement climate targets by 2030. Efforts to reach the goals have focused on raising more financial resources, on tracking progress and stimulating policy reform at national and local levels, and on innovation. This article reviews these approaches and concludes that they are indeed necessary, but not sufficient, since they do not include a focus on systematically scaling successful development and climate projects and programs aimed at achieving the SDGs and climate targets. The article goes on to present a tested approach to scaling and an example of its application in four countries. A key element of the common scaling approaches, namely the identification of a clear vision of scale, i.e., a scale target, can be linked to the SDGs and climate targets, though this has not been done in the literature or in practice so far. If the SDGs and climate targets are to be attained, it will be essential that programs and projects are systematically designed and implemented to achieve scaling pathways explicitly linked with these targets. Increased financing, tracking of progress and policy reform, and innovation will be important complements to an effective scaling approach.

Acknowledgement

The author benefitted from and gratefully acknowledges the comments on earlier drafts of this article from Alan Alexandroff, Lawrence Cooley, Richard Kohl, John McArthur, Jacob Taylor and a peer reviewer. Box 1 was prepared by Jacob Taylor.

Read the full article as a PDF:

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

The 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) represent the international community’s concern about a broad range of global development, environment and climate challenges. The SDGs’ ambition and commitment is to achieve significant progress globally in addressing these challenges with a sense of urgency and with monitorable targets. The SDGs were agreed to unanimously in 2015 by the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) and are to be attained by 2030. However, recent assessments show halfway through the 15 year period that progress so far has been too slow and incomplete to allow the SDGs to be reached globally by 2030. (Kharas and Rivard 2022; Sachs et al. 2022; United Nations 2022a) The recent COVID pandemic and the global economic crisis caused by the Ukraine war have further set back progress especially in regard to poverty and food security targets. A recent meta-analysis of the scientific evidence of the political impact of the SDGs since 2015 reveals that while there has been some limited effect of the SDGs in global, national and local political discourse, “[o]verall there is only limited evidence of transformative impact.” (Biermann et al. 2022, 798) And, as analysis in the run-up to the UN Climate Change Conference in November 2022 (COP27) demonstrated, the 2015 Paris Agreement’s climate goal of keeping global warming to no more than 1.5 C above preindustrial levels by 2050 is becoming increasingly difficult to attain in the absence of dramatic policy action and much increased investment. (Matthews and Wynes 2022; United Nations 2022b)

The common response to this shortfall in achievement of the SDGs and the Paris Agreement climate goals has been to argue for more international development and climate finance, to press for policy and institutional reform complemented by top-down mapping and monitoring of the global SDGs at national and subnational levels, and to push for more innovative solutions. These are all valid responses. I argue here, however, that these efforts are not enough. In addition, it will be essential to ensure that development programs and projects are systematically linked with and supportive of reaching the SDG and climate targets. The way to do this is to apply a ‘scaling approach’ to program and project design and implementation, where the program or project supports a scaling pathway towards a long-term vision of development impact that is explicitly linked to the appropriate SDGs or climate targets.

The scaling approach is designed to address the most common failings of the current one-off program and project approach, which promotes piloting of innovative features without a clear vision of whether, and how, successful interventions can be sustainably replicated and scaled[1]. The traditional project approach focuses on delivery of short-term program and project results rather than on creating the enabling conditions for a longer-term pathway of sustainable scaling beyond project or program end. Such short-term programs and projects fail to create the local capacity and ownership (‘localization’) to take a successful program or project forward and do not sufficiently leverage scarce funding through partnerships to achieve the scale of impact needed to achieve the SDGs and climate goals. The central contention here is that the design, implementation and evaluation of development and climate programs and projects must focus systematically on how to sustainably scale their impact and explicitly link the programs’ vision and their measurement of impact at scale explicitly to achieving the SDGs and climate goals so that these critical and urgent goals can be met in a timely manner.

The analysis here is based on the following: a review of the relevant literature; on the author’s own research into the experience of scaling development interventions over the last 15 years; and on work undertaken by the international Scaling Community of Practice[2]. The article’s focus is primarily on the SDGs and to a lesser extent on the global climate goals, but the general argument for a more explicit and systematic focus on scaling project and program impact to achieve agreed long-term national and global goals applies with equal force to addressing other global challenges, including biodiversity and early warning action.

Sections 2 to 5 of this article review the common approaches to achieving the SDGs and climate targets, their strengths and limitations. Section 2 addresses recommendations to increase the aggregate financing for SDGs and climate action. Section 3 considers top-down mapping and monitoring in support of policy and institutional reform in the form of Voluntary National Reviews (VNRs) for the SDGs and of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) for climate action. Section 4 does the same for mapping and monitoring in support of local policy and investment planning through Voluntary Local Reviews (VLRs) and Regionally and Locally Determined Contributions. Finally, Section 5 explores efforts to support innovations to help achieve the SDGs and climate goals, with a special focus on the 17 Rooms initiatives sponsored by the Brookings Institution and the Rockefeller Foundation. The purpose of these sections is to demonstrate that while common approaches to implementing the SDGs are important, they do not address the need for a systematic focus on bottom-up scaling of development and climate programs and projects. These sections set the stage for the remainder of the article beginning with Section 6 where I argue that the prevailing one-off development program and project approach and the lack of a systematic scaling approach severely limit the prospects of achieving the global development and climate goals. Section 7 introduces a pragmatic scaling framework and Section 8 provides a specific example where key elements of this framework have been applied. Section 9 concludes with a summary of the overall message of the article.

[1] See video interview with Larry Cooley (2014): “Pilots to nowhere on the rise in recent years” https://www.devex.com/news/desperately-seeking-scale-as-pilots-to-nowhere-on-the-rise-84188

[2] See the Scaling Community of Practice website: www.scalingcommunityofpractice.com

2. Increasing the aggregate financial resources devoted to the achievement of the SDGs and climate goals

Perhaps the most common response to the evident challenge of reaching the SDGs by 2030 has been a recommendation to increase the aggregate financial resources devoted to their attainment. The first recommendation of the SDG 2022 report by Sachs et al. (2022, viii) calls for “a global plan to finance the SDGs”, which would mostly rely on increased concessional and non-concessional resource flows from the developed to the developing countries, including a substantial increase of resources channeled through multilateral finance institutions. The UN’s SDG 2022 report (UN 2022a, 3) recommends “a comprehensive transformation of the international financial and debt architecture.” Based on a detailed review of development and financing trends in recent years, Homi Kharas and Charlotte Rivard (2022, 95) argue that “[a] system refresh is needed to break the cycle of deferred spending on human capital, sustainable infrastructure and nature. Without innovation and a political impetus towards renewed development financing, the prospects for sustainable development appear grim.” Other author contributions to the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation (2022) publication on UN financing stress the importance of increased climate finance, as does a recent report by the Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance[1]. In the run-up to the IMF-World Bank’s annual meetings in October 2022 there were many calls by high-level officials and experts for increases in development and climate finance, especially by the multilateral development banks (MDBs)[2].

Increased finance is clearly an essential component of any strategy to improve the chances for attaining the SDGs by 2030 and the lack of adequate finance often is a binding constraint on efforts to replicate or scale successful programs and projects.[3] Therefore, efforts to strengthen national financing policies and frameworks are very important[4], as are increases in external official and private finance (as long as they do not create unsustainable debt burdens). However, considering the experience with the impact of development assistance in the past, skepticism is warranted regarding the view that more finance on its own will be enough. Research on the effectiveness of aid has shown that while the evidence for individual projects and programs has on balance positive impacts, the results of efforts to measure the impact of aid on an aggregate, country-wide basis have been much more ambiguous, giving rise to the well-known ‘micro-macro paradox’ of aid effectiveness[5]. Many different reasons for limited effectiveness of aid at an aggregate level have been cited, including poor institutions and policies as well as instability and conflict in recipient countries. Increasing fragmentation of donor programs, declining project size and in particular the one-off nature of donor funded projects are additional reasons[6]. The lack of sustainability and scalability of the many small donor-funded projects – and the lack of effort to actually sustain and scale projects that in principle are sustainable and scalable – is likely a key reason for the apparently weak aggregate impact of aid, that will be further explored in subsequent sections.

Cichocka and Mitchell (2022) extended the analysis of constraints on development effectiveness of aid flows to the challenges faced by climate finance. They note (2022, i) that these challenges include “predictability of disbursements, affordability and concessionality of funding, provider proliferation and project fragmentation, implementation via modalities supporting recipient ownership, and the degree to which climate-related interventions are evaluated.” In their assessment, climate assistance faces even greater problems than traditional development assistance, because of “significantly lower disbursement ratios, a higher share of finance provided through debt instruments – and a rising share of loans to lower-income countries assessed as being at high risk of debt distress, a faster pace in proliferation of providers and shrinking project sizes, and fewer efforts to systematically evaluate impacts of interventions.”[7] The recent report by the European Court of Auditors of a USD $779 million climate finance program confirms these concerns, when it notes that “the initiative did not demonstrate its impact on countries’ resilience to climate change” since “sustainability was limited due to high staff turnover” and “[t]herefore, the expected evolution from capacity building and pilot activities to more scaling-up of adaptation actions reaching more beneficiaries did not take place systematically.” (European Court of Auditors 2023, 4)

In short, increases in development and climate finance will be essential if the SDGs and Paris Agreement climate goals are to be reached, but they will most likely not be enough to achieve the impact needed unless complemented by significant changes in domestic institutions and policies, and in the way projects and programs are funded and implemented with a focus on supporting scaling pathways towards the achievement of global goals and targets.

[1] Vera Songwe, Nicholas Stern and Amar Bhattacharya (2022); a core point of their paper is that development and climate goals and action have to be treated as closely interrelated challenges and opportunities and need to be considered jointly. This point is well taken, but not further pursued in this paper.

[2] See Linn (2022a) for some examples.

[3] See Lesson 11 on p. 14 of Kohl and Linn (2022).

[4] The UN’s support for integrated national financing frameworks (INFFs) aims to help countries develop improved national financing strategies (see https://inff.org). However, the INFF approach does not focus on the scaling of individual programs and projects (UNDP no date).

[5] See Nowak-Lehmann and Gross (2021). They summarize the literature on aid effectiveness as follows (193): “All in all, the third-generation studies have produced mixed results. Some studies found a positive and significant impact of aid…others found an insignificant impact… and some studies even found a negative and significant impact of aid when institutional quality is low….” They conclude (189) that “aid promotes investment in countries with good institutional quality…. Aid is ineffective in countries with unfavorable country characteristics such as a colonial past, being landlocked and with large distances to markets.”

[6] See Linn (2011). The recent analysis of donor fragmentation in World Bank (2022) noted that the number of bilateral and multilateral aid agencies had dramatically increased from 191 to 502 from 2000 to 2019. The number of official financial projects (“transactions”) more than doubled between 2000 and 2019, while the average size of a total of 222,000 projects in 2019 was only $1.4 million in 2019, decline from $2.2 million in 2000. Official development assistance (ODA) grants had an average value of only $0.8 million in 2019, about half the value of 2000.

[7] Le Houérou (2023) calls for remedies to the fragmentation of the climate finance architecture noting that there were 81 funds operating independently in the climate space in 2022.

3. Top-down mapping and monitoring in support of policy and institutional reform: Voluntary National Reviews and Nationally Determined Contributions

It was recognized from the beginning that, for global goals and targets to be realized, they had to be mapped into national development and climate targets and that progress towards these national targets had to be monitored. Starting soon after the adoption of the SDGs, a UN-led and supported effort got underway to: map the global targets into national targets, identify policies and institutions needed for their achievement, and to monitor progress at country level. This principally involved the preparation of national voluntary reviews (NVRs). The nature and purpose of these reviews, according to a UN website dedicated to NVRs, are as follows: “[R]egular reviews … are to be voluntary, state-led, undertaken by both developed and developing countries, and involve multiple stakeholders. The voluntary national reviews (VNRs) aim to facilitate the sharing of experiences, including successes, challenges and lessons learned, with a view to accelerating the implementation of the 2030 Agenda. The VNRs also seek to strengthen policies and institutions of governments and to mobilize multi-stakeholder support and partnerships for the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals”[1].

According to the UN VNR Website, since 2016 306 VNRs have been carried out, for many countries more than one. Only six countries are reported not to have carried out a VNR, among them, embarrassingly, the United States. (Sachs et al. 2022) A review of selected VNRs shows that they are generally impressive analytical documents. Some, such as the Egypt 2021 VNR[2], are progress reports that collect much relevant data on the current status and progress of SDG target indicators, linked to the countries’ national development priorities. Others, e.g., Bangladesh 2021, Denmark 2021, Indonesia 2021 and Jamaica 2021[3] in addition discuss in considerable detail policy changes required to accelerate SDG progress and cite specific programs and projects aligned with the SDGs, including some that operate at large scale[4]. The Indonesia VNR stands out because it explicitly cites a number of programs and projects that are “are easy to replicate,” “are likely to be replicated,” or “can be replicated.” One Indonesian program, the Rural Empowerment for Agricultural Development Scaling Up Initiatives (READ-SI) project, executed by the Agency for Agricultural Extension and Human Resource in partnership with the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), is reported to focus specifically on scaling up interventions to support the productivity and well-being of small holder farmers in support of SDGs 1 and 2 through a succession of projects that replicate successful components of the initial projects more widely in the country[5]. However, this explicit focus on the potential for scaling and the actual scaling of projects and programs in support of SDGs appears to be exceptional in the VNRs. This is not surprising since the Handbook for the Preparation of VNRs does not provide any guidance for the consideration of specific programs and projects and of their replicability or scalability, let alone their replication and scaling (High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development 2020).

For climate targets a parallel process of national target setting and monitoring is in place. NDCs to the achievement of climate goals are set by national governments and regularly reviewed and summarized by the UNFCCC (2022). However, as for the VNRs it does not appear that generally there are systematic links between specific climate programs and projects and the goals and actions committed in NDCs. (Linn et al. 2022)

In sum, the process and documents of the preparation of VNRs and NDCs represent largely top-down efforts to promote the achievement of SDRs at the national level, with little or no effort to support and track the implementation of SDRs through a systematic approach for replicating and scaling successful programs and projects. However, they provide important potential benefits for a bottom up scaling approach in development and climate projects and programs, by offering national-level targets that can serve as anchors for the scaling vision of individual interventions, by supporting institutional and policy changes that may support the development of successful scaling pathways for individual programs. By monitoring at the national level it can be determined if the cumulative impact of individual programs and projects results in sufficient progress towards national development and climate goals.

[1] United Nations. Voluntary National Reviews Website: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/vnrs/

[2] Egypt Voluntary National Review 2021, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/279512021_VNR_Report_Egypt.pdf.

[3] Bangladesh VNR 2021, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/26302VNR_2020_Bangladesh_Report.pdf; Denmark VNR 2021, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/279532021_VNR_Report_Denmark.pdf; Indonesia 2021, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/280892021_VNR_Report_Indonesia.pdf; Jamaica 2018, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/19499JamaicaMain_VNR_Report.pdf

[4] For example, the Denmark VNR 2021, op. cit., notes the case of a large scale effort to recycle industrial textiles (p.54).

[5] See Indonesia VNR 2021, op. cit., p. 96/7 and the READ-SI website, http://www.readsi.id

4. Local mapping and monitoring in support of local policy and investment planning: Voluntary Local Reviews

VLRs of the SDGs are similar in purpose and nature to the VNRs, but they are prepared at a subnational level. Since 2016 97 VLRs have been completed, of which 39 were prepared for developing countries[1]. A selective review of these VLRs shows that they are impressive efforts to map regional and city plans and priorities into SDGs or vice versa and to track progress over time, generally in terms of additional numbers or percentages of progress over a baseline rather than in relation to a target, e.g., the Buenos Aires VLR 2021 and the Cape Town VLR 2021[2].

However, some VLRs also highlight specific programs and projects and at times note replication and scaling towards more or less specific scale goals. For example, the Los Angeles VLR 2021 sets a target of 100 percent renewable energy for 2035 and considers alternative pathways of getting there[3]. The Bonn Germany VLR 2022 lists a number of pilot programs in support of specific SDGs and notes the potential for replication and scaling, without however indicating whether and what pathways to scale have been considered[4]. The Subang Jaya Malaysia VLR 2021 highlights a Dengue eradication program and a program for affordable housing for all, but the latter does not indicate that specific scaling pathways are considered[5]. Japan’s Shimokawa City (Japan) VLR 2018 most explicitly connects longer-term SDG-linked scale targets with programs and projects by systematically applying a “backcasting” approach[6]. This approach starts with defining, in a participatory way, the vision of where the citizens want their city to be in 2030 and then work backwards to the present and define how to get to the vision. What is not clear from the Shimokawa City VLR 2018 is how this approach was implemented for specific programs and projects. However, the basic approach is sound and can readily be mapped into the specifics of a systematic approach to scaling discussed below in Section 6.

For climate action, regional and local authorities also can play a significant role in helping to achieve national climate goals, in particular the NDCs, and some regional and local authorities have taken climate initiatives. Efforts are underway to systematically develop Regionally and Locally Determined Contributions (RLDC), as for example reflected in the “Multilevel Climate Action Handbook for Local & Regional Governments” set out in the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy (2021)[7]. However, the development and monitoring of RLDCs appears less advanced than for VLRs. Moreover, the handbook for RLDCs does not focus on linking specific local programs and projects through scaling pathways to local or national climate targets. In sum, as might be expected, VLRs and potentially RLDCs tend to have a more bottom-up approach than VNRs and NDCs, but there is no indication that they support the systematic and effective link of specific local programs and projects to local (or national) scale targets anchored in the SDGs or Paris Agreement climate goals.

[1] United Nations. Voluntary Local Reviews Website https://sdgs.un.org/topics/voluntary-local-reviews. In addition, 26 Voluntary Subnational Reviews were published since 2020; 21 of these were from developing countries. They represent countrywide reports of localization of SDGs. Global Observatory on Local Democracy and Decentralization https://gold.uclg.org/report/localizing-sdgs-boost-monitoring-reporting#field-sub-report-tab-1

[2] Buenos Aires 2022, Argentina https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/vlrs/2022-10/ba_vlr_2022_english.pdf; Cape Town 2021, South Africa https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/vlrs/2022-04/cape_town_vlr_2021.pdf

[3] Los Angeles 2021, USA https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/vlrs/2022-10/ba_vlr_2022_english.pdf

[4] Bonn 2022, Germany, https://sdgs.un.org/topics/voluntary-local-reviews

[5] Subang Yaya 2021, Indonesia https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/2021-07/VLR%20SDGs%20Subang%20Jaya.pdf

[6] Shimokawa 2018, Japan, https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-09/shimokawa-city-hokkaido-sdgs-report-en-2018.pdf; and Koike et al. 2020.

[7] See also Center for Climate Engagement website: https://climatehughes.org/locally-determined-contributions/

5. Innovation for the achievement of the SDGs and climate goals

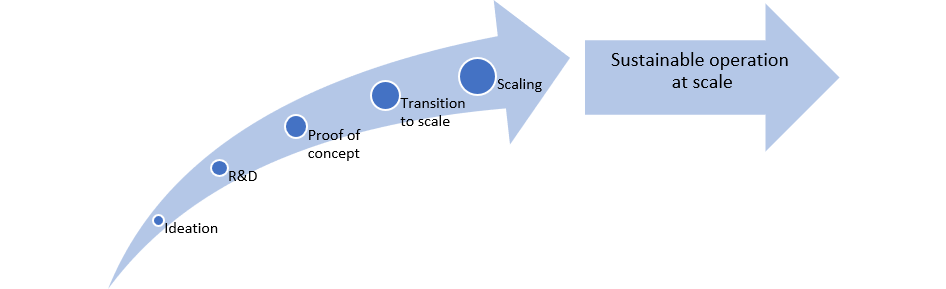

The approval of the SDGs and of the Paris Agreement Climate targets led to calls and initiatives for innovation as the way to achieving the 17 goals. New technologies, new processes and institutional solutions, new financing mechanisms, and new approaches to engage stakeholders and communities have been among the many innovative ideas propagated by experts and development organizations. Innovation marketplaces and labs, accelerators, challenge funds, hackathons and many other approaches were initiated as a means to help achieve the SDGs and the Paris Agreement climate goals[1]. Well intentioned and worthwhile as many of these calls and initiatives in support of innovation are, innovation on its own cannot produce the sustainable impact at scale that is needed if the SDGs are to be achieved. And with few exceptions, funders have stressed innovation rather than replication and scaling[2]. Most of the innovation labs and challenge funds supported by bilateral official funders have focused on the early phases of the scaling pathways – ideation, research and development, and proof of concept, rather than on the actual scaling stages – transition to scale, scaling, and operation at scale (Figure 1). Where funders do focus on scaling, they have insufficient financial resources to support scaling effectively and fail to get the main funding units in their organization (‘the mothership’) to support the innovations tested in the lab. (Jhunjhunwala and Kumpf 2022, Pasquet at al. 2023) Ways have to be found to nurture the successful innovations beyond proof of concept along scaling pathways that produce sustainable outcomes at scale.

[1] Examples of calls for innovative solutions include: “Innovation Is the Only Way to Win the SDG Race” (https://www.bcg.com/publications/2019/innovation-win-sdg-race); “Why Innovation Is Critical to Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals” (https://www.iisd.org/articles/insight/why-innovation-critical-achieving-sustainable-development-goals); “How social innovation can deliver the SDGs: six lessons for the decade of delivery” (https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/01/how-social-innovation-can-deliver-the-sdgs-six-lessons-from-the-schwab-foundation/); “SDGs, Innovation and Impact – How to Connect the Dots” (https://tfp-global.org/sdgs-innovation-and-impact-how-to-connect-the-dots/). Examples of innovation initiatives for the achievement of the SDGs include: a UN Technology Facilitation Mechanism in support of the SDGs (https://sdgs.un.org/tfm); the SDG Hub, a global SDGs network for innovation and impact (https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/sdg-hub-global-sdgs-network-innovation-and-impact); the UN Global Compact Breakthrough Innovation for the SDGs Action Platform (https://www.unglobalcompact.org/take-action/action-platforms/breakthrough-innovation); and the UNDP Accelerator Labs (https://www.undp.org/acceleratorlabs).

[2] E.g., “Most members of the DAC, i.e., bilateral official donors insufficiently invested in creating evidence about how innovations and interventions they supported in the past have and might reach scale.” (Jhunjhunwala and Kumpf 2022)

Figure 1. A stylized scaling pathway

Source: Adapted from IDIA (2017)

A particularly interesting program focused on stimulating innovative approaches for the achievement of the SDGs is the “17 Rooms” initiative, a partnership between the Center for Sustainable Development at The Brookings Institution and the Innovation team at The Rockefeller Foundation. Launched in September 2018 as an experiment to stimulate new forms of collaborative action on the eve of the United Nations General Assembly, 17 Rooms has since evolved on two tracks: (1) an annual global flagship process focused on international-scale SDG challenges; and (2) “17-X,” a widely accessible approach to help communities of all scales and geographies take practical steps toward their local SDG priorities. In all 17 Rooms processes, each Room (i.e., working group) is encouraged to target “next-step” SDG actions that are “big enough to make a difference and sized right to get done” within a 12-18 month timeframe[1]. Early iterations of the flagship process have surfaced a range of collaborative actions along a full spectrum of SDG problem solving, from expanding proven technical innovations or programs to new settings, to developing new products or tools, influencing critical policy debates, or building new and bolstering existing platforms for cooperation[2]. The examples in Box 1 provide a sense of the contribution that the 17 Rooms initiative aims to make.

[1] “17 Rooms: Rejuvenating the Sustainable Development Goals through shared action.” (ii). https://www.brookings.edu/essay/17-rooms-rejuvenating-the-sustainable-development-goals-through-shared-action/

[2] Ibid.

Box 1: Examples of actions emerging from the 17 Rooms flagship

Expanding proven technical innovations or programs to new settings:

- Inspired by Togo’s breakthrough Novissi digital cash transfer program, an array of public, private, and non-profit actors distilled frontier design principles and went on to support local leaders in Malawi and Nigeria in developing their own programs (Room 1, 2021). In the 2022 flagship process, Room 1 further developed the idea of testing and developing AI-informed cash transfer systems for greater speed and potentially and insurance-based approach.

- Data scientists, development experts, and local non-profit actors co-designed a pioneering prototype for a women’s digital data cooperative in India (Room 9, 2022)

Developing new products or tools:

- Institutional investors and independent policy experts partnered to create a new investor data tool to assess risk of forced labor in company supply chains. Technology and data partners now plan to test the prototype in 2023 (Room 17, 2021).

- Workforce experts developed the “Opportunity Metrics” framework with partner firms to help them monitor and increase job quality, mobility, and equity within companies, with special attention to low-income workers (Room 8, 2021)

Influencing high-level policy debates:

- Scientists and policy experts united to advance a high-level strategy to harmonize Africa-wide national policies on insect-based food, feed, and fertilizers (Room 2, 2022)

- Technical experts, government officials, and funding actors helped catalyze, shape, and align three independent strands of action for the global movement for digital public goods (DPGs) and digital public infrastructure (DPI): a policy agenda for Co-Develop, an international fund launched in 2021 to help countries develop inclusive, safe, and equitable DPI; the “DPG Charter,” a multi-stakeholder initiative to align and mobilize diverse stakeholders and initiatives around a compelling shared vision for DPGs; and a high-level multi-stakeholder commitment to support the development and scaling of inclusive DPI, which helped inform USD$295 million of initial pledges from various funders in September 2022.”[1] (Room 9, 2019-2021)

- Policy leaders on global climate finance developed a “breakthrough” narrative for climate finance aiming at high-level negotiations leading into COP26 (Room 13, 2021)

Building new platforms for cooperation:

- An array of global education leaders came together to launch a 12-month road map, leading up the COP28 climate summit in November 2023, for teachers and education leaders to co-create a climate-ready education system for all (Room 4, 2022)

- Gender and development experts leveraged the neutral framing of “Room 5” to create a new venue for diverse faith leaders working to advance gender equality (Room 5, 2021)

Source: Prepared by Jacob Taylor (17 Rooms secretariat member and Fellow, Brookings Center for Sustainable Development).

The strengths of the 17 Rooms approach include the clear link of innovations to the SDGs, the encouragement of cross-SDG cooperation, an inclusion of, and outreach to, a broad community of stakeholders, and a focus on actionable next steps with continued engagement by the participants following the annual convening of the 17 Rooms. At least for some of the rooms, planning for action programs in support of multiyear scaling pathways, and the continuity of engagement by participants over successive years under the 17 Rooms umbrella, also represent aspects that bode well for impact at scale. Looking ahead, it will be critical for the 17 Rooms initiative to sustain its efforts and focus systematically on achieving impact at scale not just in some of its Rooms, but as a basic principle of its engagement in all Rooms. In his article on the 17 Rooms, John McArthur (2021, 80) argues that “most of the innovations for SDG achievement will be bottom-up” and adds that “[o]ver time, a global secretariat function can amass and evaluate the collection of bottom-up actions to identify opportunities for larger scale cooperation.” A global secretariat could indeed add value in focusing on the scaling agenda, but explicit and systematic consideration of scaling also must be part and parcel of all innovation efforts that aim to support the achievement of the SDGs. The scaling up approach and principles which we turn next can serve as a helpful guide in ensuring these goals.

In the climate action space, the Global Systems Lab, a joint initiative of the Bezos Earth Fund and World Resources Institute, takes a different approach to identify and track innovative climate action in 50 specific areas in support of achieving positive tipping points that would assure spontaneous scaling of action in support of the achievement of key climate goals[1]. This approach drives a focus on action to achieve impact at scale at a systems level, but it, too, will need to be linked with a systematic focus at project and program level to ensure that they produce the required changes in the system that lead to the tipping points that the Lab has identified.

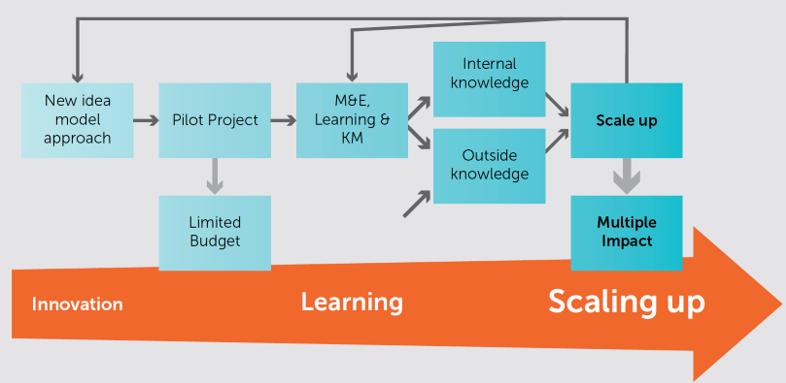

In sum, innovation is an important ingredient for any strategy to achieve the SDGs and Paris Agreement climate goals. Indeed, innovation and adaptation are part of the scaling story, not only because innovations need to be scaled to achieve the impact required to meet the goals, but also because innovation is an important aspect in the scaling process itself, as reflected in the feedback loop from scaling to innovation in the stylized graph below, Figure 2. Yet, the frequent belief that good innovation will scale on its own because “someone will pick it up and run with it” (Linn 2019) amounts to magical thinking which will usually be disappointed.

[1] See https://systemschangelab.org/ and Andrew Steer, recording https://www.scalingcommunityofpractice.com/scaling-climate-action-post-cop27/

Figure 2: Innovation, learning and scaling interact to achieve sustainable impact at scale

Source: Cooley and Linn (2014)

6. A lack of attention to the SDGs and climate targets at the program and project level

The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) – the forerunners of the SDGs – were approved in 2000 by the UN for implementation by 2015. At that time I served as Vice President for the Europe and Central Asia Region in the World Bank. I recall that the Bank’s leadership somewhat reluctantly endorsed the MDGs and that managers put up big banners listing the MDGs in their meeting rooms proclaiming the centrality of the MDGs. However, World Bank management and staff then mostly forgot about the MDGs in their consultations with governments, in the appraisal, supervision and evaluation of projects funded by the World Bank, and in much of their analytical work at country and global level.

One might conclude that those were the bad old days, or that it was just the World Bank ignoring the MDGs. However, this is not the case. Over the last 20 years, I have worked with many development organizations and interacted with governments and private sector actors. I was involved in the preparation, or review of country strategies programs and projects supported by multilateral and bilateral official development agencies, including the African Development Bank, Australian Aid, Germany’s GIZ, IFAD, UNDP, USAID and the World Bank. I also consulted with international operating NGOs, including Heifer International and Save the Children, and with foundations, including the Eleanor Crook Foundation[1]. In addition, I reviewed the relevant development effectiveness and evaluation literature (Hartmann and Linn 2008, Linn 2011) and participated in the activities of the Scaling Community of Practice over the last eight years. My conclusion is that there remains a yawning gap between the high-level declarations of support for the SDGs and the development programs and projects that are being implemented on the ground. In my experience, these projects rarely focus on linking the project goals, design, implementation and evaluation systematically and effectively with the long-term development goals, including the MDGs and SDGs.

Why are there such gaps between the SDGs, and achieving the goals, and bottom-up development projects and programs? A principal reason, in my opinion, is a preoccupation in development and climate circles with innovation as the preferred response to the challenge of development and climate change, noted in Section 5 above. The seemingly more mundane task of taking successful innovations to scale was left largely to chance, in part perhaps because in the commercial sphere, scaling appears to happen spontaneously, when of course that is not the case. Private firms spend much effort and large sums not only on innovation (research and development), but on market and supply chain research, on creating demand through advertising and promotion, on developing optimal production processes that raise quality while containing costs, on adapting products to meet evolving consumer preferences, and on mobilizing financing to support their scaling pathways. However, even in commercial scaling the difficulties of traversing the well-known “valley of death” in the early phases and of reaching customers of the “last mile” are well known, as various obstacles, including unfavorable cost structures and customers’ limited ability to pay, lack of suitable financing, government policies and regulations, etc. get in the way (Agapitova and Linn 2016).

A second reason – and one that is particularly dominant for externally, donor funded projects and programs – is the fact that development project design and implementation typically focus on getting the project or program started and funded, on implementing it according to agreed specifications and over a limited time 3–5-year time horizon, and on achieving whatever impacts the project promised to deliver. This is certainly a desirable aspect of project management, but it is not enough if one wants to make sure the project or program contributes meaningfully to the achievement of longer-term development and of climate goals at national, regional or global scale, including the SDGs. One must also ensure that a successful project or program creates the platform for subsequent sustainable scaling of development and climate impact along a pathway that is explicitly linked to an appropriate SDG or climate target. When this longer-term focus on sustainable scaling towards the SDGs is not built into project design and implementation, the development process remains stuck in one-off projects, in ‘pilots-to-nowhere’, in magical thinking where just because a project works, others – someone, whoever – will pick it up, will replicate or scale it[2]. And, therefore, it should not come as a surprise that development and climate investments bear only limited fruit and thus contribute to the shortfall in the achievement of the SDGs and climate targets.

Of course, there are exceptions to the conclusion that development and climate innovation and projects do not pay adequate attention to scaling. For example, there is the Chinese approach to development, which was widely based on experimentation with innovative solutions followed by systematic scaling of promising solutions, at times with external support, as in the case of the Loess Plateau development. (Moreno-Dodson ed. 2005, Mackedon 2012) Or take the Mexican conditional cash transfer program, Progresa-Oportunidades, which aimed for, and achieved, substantial reductions in poverty over decades of a systematically planned and implemented scaling process. (Levy 2006) Then there are the large-scale national development programs of the Indian government and of the Bangladeshi NGOs, BRAC and Grameen Bank. Moreover, some funder organizations have actively pursued scaling agendas, including vertical funds such as the GAVI, the Global Fund, the Green Climate Fund, and IFAD (Gartner and Kharas 2013), as well as programs in GIZ and USAID, albeit with varying degrees of sustained success. (Kohl 2022) But even where efforts have been, and are being made to scale up development solutions, they have generally been the exceptions and have not been directly linked to the SDGs, or, before them, to the MDGs, and the Paris Agreement climate goals.

A critical challenge therefore is to close the gap between the SDGs and development projects and programs that has been a key constraint to effective implementation of SDGs. The question is how to close this gap. As the earlier sections have demonstrated, hopefully, existing top-down approaches such as focusing on more funding, on tracking progress at global, national and local levels, and on supporting innovation are important. However, on their own they are not likely to succeed as long as a key instrument for action, namely the design and implementation of development and climate projects and programs, is not calibrated to focus systematically on achieving the enunciated long-term goals and targets. The answer then is to adopt a systematic approach to scaling the impact of proven interventions towards the achievement of one or more SDG(s). How this can be done is taken up in the next sections with a principal focus on a scaling approach for the achievement of the SDGs. A parallel argument can be made for the achievement of the climate targets but is not further pursued here.

[1] Publications based on this work include: Linn et al. (2010), Hartmann et al. (2013), Linn (2015), Agapitova and Linn (2016), Begovic et al. (2017), Chandy and Linn (2011). For donor-supported programs, see Kohl (2022).

[2] For an example of such magical thinking, see Linn (2019). For climate finance projects the problem with traditional development project practices is reinforced by fragmentation and smaller development projects (see footnote 7, above and Cichocka and Mitchell 2022).

7. Key elements of a scaling approach to support the achievement of the SDGs

Before considering the details of the scaling approach it is necessary to define what is meant by “scaling”. A people-centered definition of scaling was used by the author in earlier work (Hartmann and Linn 2008, 8): “Scaling up means expanding, adapting and sustaining successful policies, programs or projects in different places and over time to reach a greater number of people.” However, a more generic definition, which stresses a focus on a problem to be solved and on sustainable impact relative to an identified need or objective, was developed for the Scaling Community of Practice. This definition consists of: a “systematic process leading to sustainable impact affecting a large and increasing proportion of the relevant need.” (Kohl and Linn, 2022:5) The advantage of this definition is that it also applies to such areas as climate change, where targets tend not to be principally related to the number of people reached. Another strength of this definition is that it puts the focus not so much on expansion of impact from a baseline, but on the target to be reached and hence on the impact gap to be closed. Progress in scaling would therefore be measured not only relative to the baseline, but more importantly relative to the target to be reached[1]. This is a critical aspect in connection with the achievement of the SDGs, and indeed the Paris Agreement climate targets.

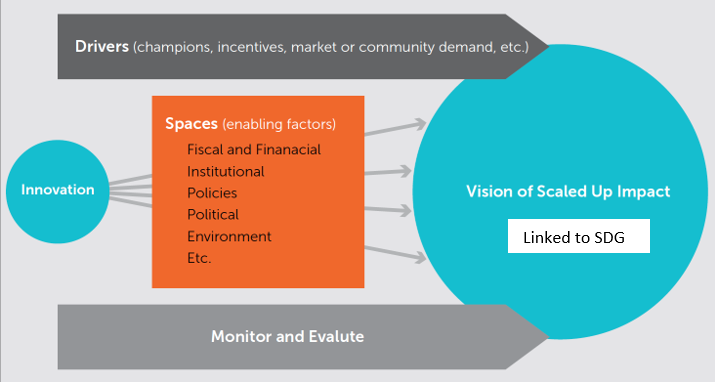

What are the key elements of a scaling approach to connect projects and programs with the SDGs? Based on the scaling efforts in which the author has been engaged over the last 15 years, and based on the experience of the Scaling Community of Practice, there are six critical steps which should be taken into account in preparing and implementing development projects and programs. These steps are briefly summarized below. They are reflected in the scaling principles and lessons developed and endorsed by the Scaling Community of Practice (2022). Key aspects of the approach are graphically shown in Figure 3 below[2].

[1] Or, as Lawrence Cooley (Cooley and Linn 2014) likes to point out: We need to look at not only the numerator (impact achieved in absolute terms), but also at the denominator (the target to be reached) in assessing the degree of progress we are making.

[2] For more detail on the scaling approach summarized here and lessons with applying it, see Cooley and Linn 2014).

Figure 3. From innovation to scale – a scaling simple scaling framework

Source: Adapted from Cooley and Linn (2014)

Step 1: Define the development problem and a long-term vision of scale to be attained, and link it to appropriate SDG target(s). Successful sustainable scaling takes time, often 10-15 years or more.

Step 2: Explore the role of an intervention (innovation, project, program):

- Assess how the intervention will address the development problem and support a scaling pathway towards the vision of scale and the SDG.

- Consider whether alternative solutions could provide better options.

- Build in a scaling perspective from the beginning – at the design stage already – and throughout project implementation.

Step 3: Assess scalability of the intervention, i.e., whether the enabling conditions for scaling prevail or how to create them since context is critical. Key enabling conditions (see Figure 2) include:

- The drivers of scaling, such as champions, incentives, demand, donor engagement; and

- The spaces to be created, or constraints to be removed to allow sustainable scaling, including political support, policy reform, creation of institutional capacity, ensuring adequate fiscal and financial resources to meet costs.

Step 4: Develop partnerships to support the achievement of scale, by assuring the necessary technical and institutional capacity, raising sufficient funding, creating political buy-in, and facilitating handoff at project end. Potential partners include private business, government and non-governmental actors at the national level, and funding and technical partners internationally.

Step 5: Pay attention to sequencing. Sequencing involves:

- Assure proper piloting/proof of concept;

- Work towards continuity and effective transitions, especially from one project to the next along the scaling pathway; this requires timely preparation of exit, handoff or repeater finance;

- Combine replication – horizontal scaling, with policy/institutional reform – vertical scaling, in appropriate sequence; and

- Adopt appropriate sequencing of financing instruments – grants early, while loans, equity and user charges later.

Step 6: Monitor and evaluate progress along the pathway and adapt as needed. Special attention should be paid during midterm reviews to the potential for scaling beyond project end and what needs to be done to put in place the enabling conditions to make scaling happen.

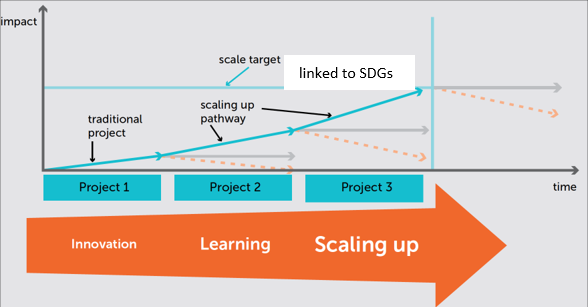

Figure 4 visualizes, again in a stylized manner, the scaling pathway as a sequence of projects and demonstrates important aspects of the scaling process presented above: the need for a scaling target linked to one or more SDGs and a notional pathway to reach it; the importance to ensure each project in effect builds a platform of enabling conditions on which the next project can in turn build; the need to ensure a smooth transition from one project to the next; and the critical link between sustainability and scaling – without sustainability scaled up impact will not be maintained – see the yellow dotted arrows, and sustainability without scaling will not reach the target.

Figure 4: A sequence of projects is usually needed to achieve sustainable scale

Adapted from Cooley and Linn (2014)

Three common questions arise: (a) How does scaling related to systems change? (b) How does scaling address the challenge of reaching marginal and hard-to-reach communities, i.e., how to go “the last mile”? and (c) How will development practitioners react to being confronted with an additional challenge – the scaling challenge – they would need to address. On the first question, scaling and system change are closely related[1]. As noted above, effective scaling requires an understanding of the ecosystem of enabling conditions. They either have to be accepted as they are, i.e., as constraints to be accepted and adapted to as best as possible, which is often the case for smaller actors, or they can be changed through suitable reforms to allow the scaling process to proceed unimpeded, which larger, politically more influential actors can strive to achieve. From the perspective of aiming to achieve the SDGs, institutional and policy reform is generally desirable to permit scaling to happen. Therefore, system change is an integral part of scaling. However, system change – i.e., institutional and policy reform – generally also requires that there is a good understanding of what the potential scaling pathways are and what constrains them, and a close watch is needed over whether the reforms as implemented actually help or perhaps hinder the scaling process. Moreover, institutional and policy reform generally involve many of the same aspects as scaling: they have to have clear visions of impact, they must take account of the ecosystem within which they take place, they usually must be implemented in a sequence of steps or projects that have to be organically linked and sequenced, e.g., legislation is not enough. However, implementing regulations and enforcement through the judicial system are also needed.

The second question regarding the “last mile” highlights an important challenge for any development effort, including any scaling program. Addressing the needs of the “hard to reach” or of the marginal communities often requires special and innovative interventions and institutional approaches. It generally has to involve intensive community outreach and participation, and it may be more costly than dealing with mainstream social groups. However, to reach these communities basically requires the same six steps as any other scaling pathway, while recognizing that the hurdles for successful outcomes are frequently higher. Moreover, one needs to recognize that there may be a tension between the scale goals of reaching as many people as possible on a national scale and reaching the “last mile” groups of people. Focusing on the latter goal may mean that less progress is made on the former given higher costs as well as resource and capacity constraints – a tradeoff that is best addressed explicitly and transparently as part of the consideration of a scaling pathway in designing specific development programs and projects.

Turning then to the third question regarding the reaction of development practitioners to the scaling challenge, innovators and project teams often feel overloaded with expectations and requirements that they are to meet in getting their interventions off the ground, accepted by public and private stakeholders, and financed by potential funders. Therefore, the expectation of adding additional requirements to justify interventions is often looked at skeptically by practitioners. However, the six steps above can be taken at different levels of depth of analysis, depending on the size and complexity of the intervention and the resources available for planning, implementation support and monitoring and evaluation. The most important aspect of the steps is to change the mindset, so innovators and project teams consider the scaling dimension and the potential link to the SDGs from the beginning and explore the implications of the above six steps at least in general terms. The next section presents an example of how the scaling dimension can be incorporated into the assessment of a funder’s country program and specific projects.

Finally, it must be noted that the traditional approaches to scaling, whether the one presented here or those developed by other researchers and practitioners, do not focus specifically on the SDGs (or Paris Agreement climate targets) as the goals that define the vision.[2] This is also the case with the example we turn to next. Bringing the SDGs and climate targets more explicitly and systematically into the scaling agenda remains a challenge yet to be tackled in practical application.

[1] This relationship is further explored in Kohl (2021). The close interrelationship between scaling and systems change is also reflected in the common notion of ‘horizontal’ and ‘vertical’ scaling, where the former refers to expansion of program impact across more people or wider geographies, while the latter refers to institutional and policy change required to achieve the scale goals.

[2] See the references in Kohl and Linn (2022).

8. A practical example of how to incorporate scaling in project and program analysis

In 2016/17 the author applied the scaling approach presented in the previous section in a review of four UNDP country programs – Bosnia and Herzegovina, Egypt, Moldova, and Tajikistan, in cooperation with UNDP technical staff and project teams[1]. This section summarizes the results of the indicative overall assessment of the UNDP’s approach to scaling and the link of its programs to the SDGs, based on an in-depth scaling review of 20 projects and a more high-level review of 9 additional projects in the four countries. The projects covered extend over a wide range of sectors and thematic areas, including local and community governance and local area development; energy, environment, bio-energy, and energy efficiency; disaster risk management; legal and judicial reform; HIV/AIDS, TB and Malaria; governance; ICT; and border management. The research involved in-depth semi-structured interviews with project teams and UNDP country managers in the four countries. The analysis was presented in country reports and in an overview paper with a summary of findings for all countries published in a Brookings Working Paper[2].

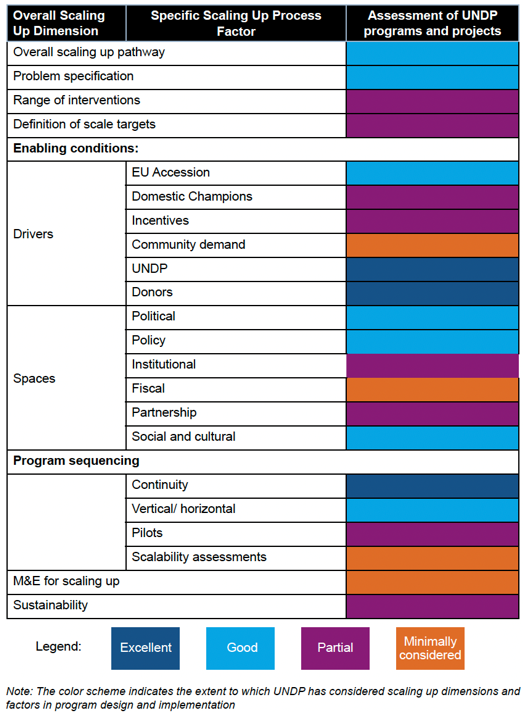

Table 1, below, summarizes the overall assessment by key scaling elements. It shows a qualitative rating of how effectively the projects applied key elements of our scaling approach, with colors representing more or less successful application – dark blue “excellent”, light blue “good”, purple “partial”, and orange “minimally considered”. The criteria from top to bottom include the extent to which the projects formulated a clear long-term vision and targets, supported a well-defined and tested set of interventions, paid attention to appropriate drivers and spaces, and focused on effective sequencing, monitoring and evaluation (M&E) and sustainability. The summary ratings are based on ratings for each of the criteria for each of the projects reviewed and then aggregated across all projects.

[1] Begovic et al. (2017). The remainder of this section draws on this source; a comparable approach was also applied in an assessment of IFAD’s scaling experience (Linn et al. 2010, and Hartmann et al. 2013) and in a review of AfDB country assistance strategies (Linn 2015)

[2] Begovic et al. (2017)

Table 1: Overall assessment of UNDP’s scaling approach in four countries, 2016

Source: Begovic et al. (2017)

The assessment shows that:

- UNDP and other donors were important proponents for scale and UNDP excelled in terms of continuity of its engagement. However, hand-off to other partners at project end or bridging to follow-up UNDP projects was frequently a major issue.

- UNDP projects performed well in identifying the development problems and overall scaling pathways, in drawing on EU accession as a key driver (where relevant), in considering political, policy and social factors, and in addressing both horizontal and vertical dimensions of scaling. UNDP, however, did not focus explicitly on achieving the SDGs in project design and implementation.

- UNDP projects did less well in considering alternative interventions, in identifying scale targets and linking them to SDGs, in considering champions and incentives among scaling drivers, and in pursuing partnerships, following up on pilots and considering sustainability.

- UNDP projects generally did not substantially address community demand and fiscal constraints and did not seriously assess scalability or pursue scaling in its monitoring and evaluation practice.

- Among the better-designed and more successfully implemented projects from a scaling perspective were two HIV/AIDS, TB and malaria projects in Tajikistan and Bosnia and Herzegovina, which UNDP implemented for the Global Fund, a project supporting the abolish of female genital mutilation in Egypt and a legal reform project in Tajikistan.

- UNDP country managers and project teams generally welcomed the focus on scaling and appreciated the framework of analysis for the scaling review of their programs.

Overall, the assessment concluded:

“[W]hile scaling up is now part of UNDP’s corporate strategy, a more systematic operational approach to scaling up in its country programs will be important, if UNDP is to play the critical transformational role in helping to achieve the SDGs that it has assigned to itself” (Begovic et al. 2017, 5).

9. Conclusion

The example in the previous section demonstrates an important point: First, good development program design and implementation practice already embodies important elements of a scaling strategy, and many organizations already have examples where scaling happens spontaneously. So, linking development programs and projects with the SDGs through a scaling approach is not ‘rocket science’. But a scaling strategy will require a change in mindset in the way actors, innovators, implementers, funders, managers and staff function. It will require the following: that development institutions – whether in the public, private or non-governmental sectors, whether they are funders or implementers – systematically internalize the scaling agenda and its link to the SDGs; and climate targets as part of their project and program design, provide implementation and evaluation. The Scaling Community of Practice has begun a deliberate effort of supporting this process of institutional internalization in a number of ways including: by developing generally applicable scaling principles and lessons (Scaling Community of Practice 2022), by exploring how government institutions can institutionalize the scaling of innovative ideas that are brought in from the outside (Igras et al. 2022); and by undertaking research on mainstreaming scaling in funder organizations. (Cooley and Linn 2022, Kohl 2022, Linn 2022b).

But much remains to be done. Ultimately, all efforts to achieve the SDGs and climate targets must complement each other: financial resource mobilization, tracking progress and policy reform at national and local levels, innovation, and the systematic scaling of development interventions that have been shown to work. Indeed, scaling is often constrained by insufficient financial resources, by policy and regulatory barriers, by insufficient attention to monitoring and evaluating progress, and by insufficient innovation in implementing scaling pathways. However, it is also true that at project and program level there has to be a systematic focus on scaling solutions that work and are explicitly linked to the SDGs and climate targets. This is necessary if the world is not to fall short in its achievement of its critical development and climate goals.

Works Cited

Agapitova, N. and J. Linn. 2016. “Scaling Up Social Enterprise Innovations.” Global Economy and Development Working Paper Nr. 95. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/research/scaling-up-social-enterprise-innovations-approaches-and-lessons/

Begovic, M., J. Linn, and R. Vrbensky. 2017. “Scaling up the impact of development interventions: Lessons from a review of UNDP country programs.” Global Economy & Development Working Paper 101. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/global-20170315-undp.pdf

Biermann, F., Hickmann, T., Sénit, CA. et al. 2022. Scientific evidence on the political impact of the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat Sustain 5, 795–800. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-00909-5

Chandy, L. and J. Linn. 2011. “Taking Development Activities to Scale in Fragile and Low Capacity Environments.” Global Working Paper No. 41. Brookings. http://www.brookings.edu/research/papers/2011/09/development-activities-chandy-linn

Cichocka, B. and I. Mitchell. 2022. “Climate Finance Effectiveness: Six Challenging Trends.” Policy Paper 281. Center for Global Development. https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/climate-finance-effectiveness-six-challenging-trends.pdf

Cooley, L. and J. Linn.2014. “Taking Innovations to Scale: Methods, Applications and Lessons.” R4D and MSI. https://www.scalingcommunityofpractice.com/advancing-change/

Dag Hammarksjöld Foundation. 2022. “Financing the UN Development System: Joint Responsibilities in a World of Disarray.” https://financingun.report/sites/default/files/2022-09/DHF-Financing-the-UN-Development-System-2022.pdf

European Court of Auditors. 2023. “The Global Climate Change Alliance(+): Achievements fell short of ambitions”. Special Report 04. https://www.eca.europa.eu/Lists/ECADocuments/SR23_04/SR_Climate_change_and_aid_EN.pdf

Gartner, D. and H. Kharas. 2013. “Scaling Up Impact: Vertical Funds and Innovative Governance.” In L. Chandy, A. Hosono, H. Kharas, and J. Linn, eds. 2013. Getting to Scale: How to Bring Development Solutions to Millions of Poor People. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. http://www.brookings.edu/research/books/2013/gettingtoscale

Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy (2021)[1]. “The multilevel climate action playbook for local and regional governments.” https://www.globalcovenantofmayors.org/press/the-multilevel-climate-action-playbook-for-local-and-regional-governments/

Hartmann, D., H. Kharas, R. Kohl, J. Linn, B. Massler, and C. Sourang. 2013. “Scaling Up Programs for the Rural Poor: IFAD’s Experience, Lessons and Prospects (Phase II).” Global Working Paper 54. Brookings. http://www.brookings.edu/research/papers/2013/01/ifad-rural-poor-kharas-linn

Hartmann, A. and J. Linn. 2008. “Scaling Up: A Framework and Lessons for Development Effectiveness from Literature and Practice.” Wolfensohn Center Working Paper No. 5. Brookings. http://www.brookings.edu/research/papers/2008/10/scaling-up-aid-linn

High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development. 2020. “Handbook for the Preparation of Voluntary National Reviews. 2021 Edition.” UNDESA. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/27024Handbook_2021_EN.pdf

IDIA. 2017. “Insights on Scaling Innovation.” The International Development Innovation Alliance. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/6295f2360cd56b026c257790/t/62a1d43829d380213485d4f9/1654772794246/Scaling+innovation.pdf

Igras, S., L. Cooley, and J. Floretta. 2022. “Advancing Change from the Outside In: Lessons Learned About the Effective Use of Evidence and Intermediaries to Achieve Sustainable Outcomes at Scale Through Government Pathways.” Scaling Community of Practice. https://www.scalingcommunityofpractice.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Advancing-Change-from-the-Outside-In-1.pdf

Jhunjhunwala, P. and Benjamin Kumpf. 2022. “OECD Scaling Learning Journeys Series: Scaling Innovation, Scaling Development Outcomes.” International Development Innovation Alliance. https://www.idiainnovation.org/resources/oecd-scaling-learning-journeys-series-scaling-innovation-scaling-development-outcomes

Kharas, H. and C. Rivard. 2022. “The yawning gap between SDG attainment and international development financing.” In “Financing the UN Development System: Joint Responsibilities in a World of Disarray.” Dag Hammarksjöld Foundation. https://financingun.report/sites/default/files/2022-09/DHF-Financing-the-UN-Development-System-2022.pdf

Kohl, R. 2021. “Scaling and Systems: An Issue Paper.” Scaling Community of Practice. https://www.scalingcommunityofpractice.com/wp-content/uploads/bp-attachments/8666/Scaling-and-Systems-Change-Issues-Paper.pdf

Kohl, R. 2022. “Exploratory Study of Mainstreaming Scaling in International Development Funders: A Summary of Findings and Recommendations for the Scaling.” Scaling Community of Practice. https://www.scalingcommunityofpractice.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Exploratory-Study-of-Mainstreaming-Scaling.pdf

Kohl, R. and J. Linn. 2022. ”Scaling Principles.” Scaling Community of Practice. https://www.scalingcommunityofpractice.com/wp-content/uploads/bp-attachments/8991/Scaling-Principles-Paper-final-13-Dec-21.pdf

Koike, H., F. Ortiz-Moya, Y. Kataoka, and J. Fujino. 2020. “The Shimokawa Method for Voluntary Local Review”. Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES). https://www.iges.or.jp/en/publication_documents/pub/training/en/10779/Shimokawa+Method+Final.pdf

Le Houérou, P. 2023. “Climate funds: time to clean up.” FERDI Working Paper 320. https://ferdi.fr/dl/df-z4LdsA8Y7stAvmESarbZ1jGQ/ferdi-wp320-climate-funds-time-to-clean-up.pdf

Levy, S. 2006. Progress against Poverty: Sustaining Mexico’s Progresa-Oportunidades Program. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Press. http://www.brookings.edu/events/2007/01/08poverty

Linn, J. 2011. “Scaling Up with Aid: The Institutional Dimension.” In Homi Kharas et al. (2011). Catalyzing Development: A New Vision for Aid. Brookings: Washington, DC. https://www.brookings.edu/book/catalyzing-development/

Linn, J. 2015. “Scaling up in the Country Program Strategies of Aid Agencies: An Assessment of the African Development Bank’ Country Strategy Papers.” Global Journal of Emerging Market Economies 7(3), pp. 236-256 http://eme.sagepub.com/content/7/3/236.abstract

Linn, J. 2019. “Scaling up development impact — the opportunities and challenges.” Devex Opinion. https://www.devex.com/news/opinion-scaling-up-development-impact-the-opportunities-and-challenges-95950

Linn, J. 2022a. “Expand multilateral development bank financing, but do it the right way.” Future Development Blog. The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2022/11/29/expand-multilateral-development-bank-financing-but-do-it-the-right-way/

Linn, J. 2022b. “Hardwiring the Scaling-up Habit in Donor Organizations.” Future Development Blog. The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2021/12/16/hardwiring-the-scaling-up-habit-in-donor-organizations/

Linn, J. and L. Cooley. 2022. “Mainstreaming the Scaling Agenda in Development Funder Organizations: A Review Concept Note.” Scaling Community of Practice. https://www.scalingcommunityofpractice.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Concept-Note-Mainstreaming-Scaling-for-distribution.pdf

Linn, J, G. Raisssova, and Turdakun Tashbolotov. 2022. “Supporting Regional Actions to Address Climate Change as a Cross-cutting Theme under CAREC 2030: A Scoping Study.” Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation Program. https://www.carecprogram.org/uploads/CAREC_MC_2022_4_Climate-Change-Scoping-Study.pdf

Linn, J., A. Hartmann, H. Kharas, R. Kohl, and B. Massler. 2010. “Scaling Up the Fight Against Rural Poverty: An Institutional Review of IFAD’s Approach”, Global Working Paper No. 39, Brookings. http://www.brookings.edu/research/papers/2010/10/ifad-linn-kharas

Mackedon, J. 2012. “Rehabilitating China’s Loess Plateau.” In J. Linn, ed. Scaling Up in Agriculture, Rural Development, and Nutrition. 2020 Focus 19. IFPRI. 2012. https://www.rfilc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/IFPRI__Scaling__Up__Linn__2012.pdf

McArthur, J. 2021. “Make Room(s) for Change.” Horizons. Number 19, Summer 2021. CIRSD. https://www.cirsd.org/files/000/000/008/98/d9a257b35a19f73bc8f22a6d3820f94aa5875cfb.pdf

Matthews, H.D. and S. Wynes. 2022. “Current global efforts are insufficient to limit warming to 1.5°C.” Science, Vol 376, Issue 6600, pp. 1404-1409 (June 2022). https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abo3378

Moreno-Dodson, B., ed. 2005. Reducing Poverty on a Global Scale. World Bank. https://books.google.com/books?id=NcyBrdarbtAC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

Nowak-Lehmann, F. and E. Gross. 2021. “Aid effectiveness: when aid spurs investment.” Applied Economic Analysis, Vol. 29 No. 87, 2021 pp. 189-207 https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/AEA-08-2020-0110/full/pdf?title=aid-effectiveness-when-aid-spurs-investment

Pasquet, A., M. Agarwal, and B. Kumpf. 2023. “OECD Scaling Learning Journeys Series: What works to design and manage Challenge Funds so that the chosen innovations can reach impact at scale?”. International Development Innovation Alliance. https://www.idiainnovation.org/resources/oecd-scaling-learning-journeys-series-what-works-to-design-and-manage-challenge-funds

Sachs, J. D., G. Lafortune, C. Kroll, G. Fuller, and F. Woelm. 2022. “Sustainable Development Report 2022.” Bertelsmann Stiftung, Sustainable Development Solutions Network. Cambridge University Press. https://s3.amazonaws.com/sustainabledevelopment.report/2022/2022-sustainable-development-report.pdf

Scaling Community of Practice. 2022. “Scaling Principles and Lessons.” https://www.scalingcommunityofpractice.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Scaling-Principles-and-Lessons_v3.pdf

Songwe, V. N. Stern and A. Bhattacharya. 2022. “Finance for climate action: scaling up investment for climate and development.” Report of the Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance. https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/IHLEG-Finance-for-Climate-Action.pdf

UNDP. No date. “Development Finance Assessment Guidebook”. https://inff.org/assets/resource/undp-dfa-guidebook-d4-highresolution-(002).pdf

UNFCCC. 2022. “Nationally determined contributions under the Paris Agreement. Synthesis report by the secretariat”. https://unfccc.int/documents/619180

United Nations. 2022a. “The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2022”. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2022/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2022.pdf

United Nations. 2022b. “Keep the 1.5°C goal alive, experts and civil society urge on ‘Energy Day’ at COP27.” UN News. (November 2022). https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/11/1130622

World Bank. 2022. “Understanding Trends in Proliferation and Fragmentation for Aid Effectiveness During Crises”. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/ef73fb3d1d33e3bf0e2c23bdf49b4907-0060012022/original/aid-proliferation-7-19-2022.pdf