The G20 at the Frontier of Creating New Global Debt Management Processes Urgency, Ambition, and Geopolitical Adjustments

For the CWD, the key question for 2023 is:

Will the successful Bali G20 Summit become an enduring turning point, ratcheting up the level of involvement of all G20 member countries in increasing ambition and the delivery of outcomes?

Or, will Bali be a blip , a “brief shining moment” that fades into memory as the world returns to war, geopolitics recedes again into confrontational narratives and the capacity of the global leadership to address systemic challenges wanes?

The G20 has proven to be a platform in which geopolitical adjustments can occur and where progress on global governance does happen. The CWD has chosen to focus on the global debt crunch not only because it is vital to global stability but also because there are opportunities for China and the US to work together on global debt, which CWD believes could help shift the dynamics of geopolitics. And in doing so CWD can facilitate stronger global cooperation in addressing global challenges. (See End Note: “China-West Dialogue: Origins, Principle and Purpose”.)

CWD Recommendations:

- G20 should further develop the Common Framework for Debt Treatment Beyond the Debt Service Sustainability Initiative(DSSI) which they established in 2020. With support from all G20 member governments, the objective would be to make the Common Framework a go-to-process for achieving financial health for both vulnerable low- and middle-income developing countries, with processes and capacities to handle multiple sovereign debt cases expeditiously and link them to sustainable longer term development trajectories.

- In 2022 the G20 Leaders agreed at their Bali Summit to step up Common Framework implementation efforts, requiring new processes, procedures and principles for both debt management and development finance for countries vulnerable to debt distress.

- In addition, the Bali Summit proposed that the deteriorating debt situation in vulnerable middle-income countries could be addressed by similar multilateral coordination processes involving all official and private bilateral creditors in swift action to respond to their requests for debt treatments.

- The new informal High-Level Debt Roundtable being convened by the India G20 presidency on February 17 with support from the IMF and the World Bank should be positioned as the G20 policy forum on Global Debt Management for the world.

- By expanding and reinvigorating the G20 Common Framework, the High-Level Roundtable on Global Debt Management would become the global nexus point for all the relevant public and private sector financial players and for organizing the necessary data and conceptual and analytical frameworks to forge longer term sustainable development trajectories from short-term sovereign debt crises.

- By connecting debt payment workouts to strong longer term investment programs articulated as national development narratives aligned with the SDGs and the Paris Agreement as a steppingstone toward achieving better global futures, the process would be designed to avoid austerity traps triggering adverse social impacts and making debt rescheduling packages politically unsustainable.

- The current discussions around the reform of the MDBs focuses on prioritizing longer term social and climate goals and mobilizing private resources as well as official development assistance. This mix of multilateral, bilateral and private finance in the past has generated inequalities between creditors which need to be addressed as China looms as the largest bilateral creditor in global finance.

- Relying now on the MDBs to power the flow of development finance requires avoiding actions which impair their credit ratings and thus their real time operational viability, and capital increases may be limited by the current budgetary and fiscal contexts of significant replenishment countries. But their role in catalyzing private finance in a world in which domestic savings, national public development banks, pension funds and bond issuers and holders are major sources of potential funding, could change the global financial landscape.

- As a result, the newly strengthened G20 Common Framework for the High-Level Debt Roundtable would have to be broad and focused, inclusive and manageable, politically astute and operationally effective. The comprehensive and inclusive processes involved would require groundbreaking changes that will extend from one G20 presidency to another and require continuous and complex inter-institutional arrangements for data flows and financial analysis. There could be a Common Framework Executive Group to manage implementation, conducive to bringing technical and political dynamics together in a fruitful expeditious process under the oversight of the G20 High Level Debt Roundtable.

- The G20 Debt Roundtable will need to take a fresh look at basic principles for managing global debt in both the short and long run. The principles that need review and strengthening are: coordination mechanisms, debt transparency and full disclosure of relevant information, comparability of treatment, stronger and quicker debt governance in both creditor and debtor countries, timely detection of solvency problems and rapid execution up front of debt-stabilizing policies, means for ensuring private sector participation, assessment of the potential impact of climate change on debt sustainability and opportunities for investment, enterprise development and employment in green growth.

- The G20 might be assisted by study groups in the T20 to work on these principles and report back to the G20 iteratively as progress is made during the Indian G20 presidency and beyond.

CWD Note on the Context: Transition Moment for Debt Management

Debt Management, Development and Investment:

As the creation of the G20 Leaders’ Summit in 2008 responded to a financial crisis with global impact, so the responses by the G20 to the impact on poor countries of the global COVID pandemic have set in train a reordering of global governance arrangements in the treatment of debt problems, and potentially in development finance more generally.

In 2020, beginning with a temporary debt moratorium, the Debt Service Sustainability Initiative (DSSI), the G20 in conjunction with the Paris Club, established a Common Framework (CF) for Debt Treatments beyond the DSSI. Then in 2022, the Bali G20 Leaders’ Summit agreed to implement a similar approach to the debt problems of vulnerable middle -income countries.

The G20 processes leading up to the New Delhi Summit in September 2023 now have the task of setting out the vision, instruments and the architecture for making these initiatives into a well -functioning new Global Debt Management process embracing both official and private debt and including new creditors with traditional donors.

Progress in developing the debt restructuring and refinancing processes under an expanded Common Framework and applying them to cases has been slow. The challenge for the new Common Framework now is that it should operate across many countries at once and at speed.

Only four countries so far have entered into negotiations with creditor groups under the umbrella of the CF – Chad, Zambia, Ethiopia and Ghana. These processes have taken time to put in place and to generate final packages.

It is in the context of the major move forward in Bali that thinking and discussions are in progress on the implementation of a new Common Framework in the G20 but also in the context of Bretton Woods processes and global finance summits, such as the one proposed by President Macron of France for June 2023 to stimulate more private development finance for the Global South.

At the same time, US Treasury Secretary Yellen is calling for MDB reform, with debt treatment on that agenda. These coming months, ahead of and at the G20 Leaders meeting in New Delhi in September, will be critical, with the role of China in the emerging new architecture and in MDB governance as central. (China, as a G20 member, made the largest contribution to the DSSI, providing 60 per cent of the DSSI relief while holding only 30 percent of DSSI claims of the 47 participating countries).

Secretary Yellen announced in mid-January a planned trip to Beijing in the near future, welcoming a return trip by her Chinese counterparts. Hopefully, this schedule will be maintained, with its opportunities to reach understandings on China’s shared ownership and leadership in a new international debt treatment regime and on collaboration among MDBs in this context, including the AIIB in Beijing and the NDB in Shanghai.

At the Bali G20 Summit, China requested a footnote to paragraph 33 of the Leaders’ Declaration to register its divergent views on debt issues, emphasizing the importance of including debt treatment by multilateral creditors like MDBs. China is maintaining this position, still under discussion in the G20, in current debt negotiations with Sri Lanka. At issue here is the preferred creditor status of the MDBs and their capacity to leverage funding from bond markets around the world. Greater understanding of China’s perspectives on debt practice and the reasons for them need to be considered and balanced by recognition in China of the new context for global finance and its complexity, urgency and constraints.

The World Bank and the IMF had engaged in debt reduction in the context of HIPC and the MDRI, but with special funding to do so from bilateral donors. Their traditional role has been to provide new financing for adjustment programs. From that perspective, participating in debt reduction would test the credit rating of the MDBs at a point when the expanded scope of the Common Framework should be bringing more debt vulnerable countries into active and expeditious negotiations with creditor groups and delivering outcomes which clearly improve sustainable medium term growth prospects.

With these historic shifts underway in global governance of debt and development finance, there is thus a set of fundamental issues to be addressed and integrated into a Common Vision for an Expanded Common Framework, and an architecture for enabling its work at the scale and pace envisaged at Bali. Hopefully, such a common vision will be possible during the first G20 High Level Roundtable on debt to be held on February 17th.

At the core of the debt treatment operations under a new Common Framework will be the relationship between debt reduction “haircuts” and new development financing. Optimal outcomes may well suggest less “haircutting” and more new financing for the investments needed to generate a medium-term sustainable growth prospects that produce medium term financial and environmental sustainability[1]. In other words, a sustainable exit from over-indebtedness comes via shared social and economic progress and spreading well-being, with adjustment processes strengthening the political viability required for these processes to succeed[2].

Ambitious lending programmes would finance ambitious reform programmes. In these times, such growth processes may be more local and more inclusive than in the era of export-led growth, with time horizons stretching over longer periods and with domestic public investments in public goods and infrastructure that support small and medium size enterprises and attract foreign investors and asset managers to be part of such longer-term stories (cf Green, Social, Sustainable and Sustainability-Linked Impacts – GSSSI) [3]. Private creditors could invest in instruments that allowed them to offset participation in “haircuts” via returns available from stronger economic recoveries (as proposed by Lazard Sovereign Debt Advisory Group, see References below).

Debt Sustainability Analysis (DAS), as currently formulated by the IFIs would need to be adapted to such growth patterns, with a shift from macroeconomic targets to the definition, implementation and scaling up of medium-term structural programmes. The G20 Sustainable Finance Roadmap and Sustainable Finance Working Group (SFWG) provide points of concordance and coherence here (3). At the national level, this approach would embody the basic organisational principle for financing the SDGs set out in Paragraph 9 of the Addis Ababa Action Agenda: Cohesive nationally owned sustainable development strategies, supported by integrated national financing frameworks, will be at the heart of our efforts[4].

The new galaxies of creditors and development finance providers require a “large tent “of participants in such debt treatment and finance arrangements, with implicit and explicit geopolitical adjustments in participation and leadership.

It is the new pattern on the creditor side of developing country debt stocks that is compelling the renewal of debt treatment architecture and processes.

In an age when official lending by major Western countries and the traditional International Financial Institutions constituted the bulk of developing country debt stocks, the informal processes of the Paris Club of official creditors, run out of the French Treasury with data supplied by the OECD and World Bank creditor and debtor reporting systems respectively, could work efficiently, essentially via rescheduling with no relief in net present value terms.

Adaptations were required however by major structural evolutions such as the advent of the Eurobond market and syndicated international bank lending in the 1970s, with crises generated by the recycling of oil surpluses and the boom in official export credit lending to developing countries in that decade. Ultimately, a systemic international banking crisis required a new resolution instrument in the form of “Brady Bonds”, guaranteed by the US Treasury, which were available to troubled US banks ready to take a “haircut” on the value of qualifying loan stocks. The Institute of International Finance (IIF)was founded at that time to assist leading US banks to navigate the banking crisis. It is now a global association of the financial industry writ large with some 400 members from 60 countries

The next major debt crisis, in the form of developing country distress in the 1980s following the 1980 “Volcker hike” in interest rates, again ultimately required resolution in the form of the 1996 Highly Indebted Poor Countries Initiative (HIPC) which was enhanced at the 1999 Cologne G8 Summit, and applied to some 39 poor countries, of which 36 countries reached completion point. In 2005 the HIPC Initiative was supplemented by the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative which, with indirect donor support, provided 100 percent relief for HIPC countries on eligible debts to the IMF, World Bank and African Development Fund.

Meanwhile, operating outside the Paris Club, China had been rescheduling maturities of interest free official loans from 1975 and then in 2000 began regularly announcing write offs for HIPCs and low-income countries on these loans and rescheduling maturities on China Export Import Bank loans, with some reductions in interest rates.

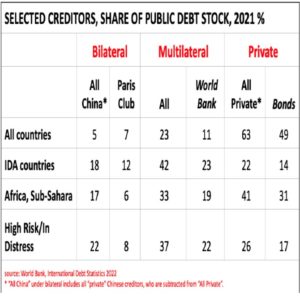

As Paris Club members and China now join together under the umbrella of the G20 Common Framework, the suppliers of finance to developing countries have multiplied in form and number. Bond markets now account for 49 percent of total Public and Publicly Guaranteed debt stocks of developing countries, compared with multilaterals at 23 per cent (World Bank only, 11 percent), Paris Club members (bilateral) at 7 per cent and China at 5 percent.

For IDA countries, these numbers are bonds 14 per cent , multilaterals 42 per cent (of which WB 23 per cent), bilateral Paris Club donors 12 per cent and China 18 per cent.

SOURCE: Deborah Brautigam (2023), CWD January 12,2023, revised.

For High Risk and in Debt Distress Countries the numbers are bonds 17 percent, multilaterals 37 percent (of which WB 22 percent ), bilaterals 8 per cent and China 22 percent.

For Sub Saharan Africa, the numbers are: bonds at 31 per cent, multilaterals at 42 per cent (WB 19), Paris Club 6 percent and China 17 per cent. The low shares of Paris Club members reflect the large share of grants in their bilateral development finance. The private international banking industry remains active, accounting for 14 percent of guaranteed debt stocks, including 11 percent of Sub-Saharan African debt stocks. Within the range of actors involved, some current features deserve note:

Multilateral Development Banks:

The current movement to reform the MDBs is largely oriented to framing their activities around climate smart development strategies, programs and projects (e.g. the Bridgetown Agenda). This focus refers to the new development narratives emerging from the literature cited above and their implications for debt treatment outcomes.

At the same time the case is being made that the MDBs are under-utilizing the capital adequacy of their balance sheets, and specifically forgoing the lending capacity available from counting callable capital as a full part of their capital base. The problem though with this case, is that in reality, ‘callable capital’ in fact has to be allocated via normal budgetary processes in legislatures, just as any other capital increase (see references below). Against that background, the lending capacity of the MDBs remains constrained by the budgetary and legislative processes in the countries where such battles are hard fought and at the same time influence the burden sharing calculations of all shareholders.

Hence the proposition that the MDBs could generate hundreds of billions more in development finance seems unrealistic given current domestic political pressures and the restricted fiscal space in replenishment countries. The role of the MDBs and the IMF in the new Common Framework in the realm of debt treatment would be to provide the ambitious new lending required as the most important component of debt treatment packages with debt haircuts by other official and private lenders encouraged by compensation from future growth. This role would require much more resources and greater coordination among them than is now the case on the ground. Such coordination in the new Common Framework must include the AIIB in Beijing and the NDB in Shanghai.

Bond Markets:

With bond markets now accounting for half of publicly guaranteed debt stocks, and 33 percent of projected debt service for DSSI countries in 2024 (more than China at 25 per cent), the interests and coordination of bondholders become crucial. The Institute for International Finance (IFF) thus has a fundamental role to play in these new Common Framework operations, including on the data side where it is facilitating private sector contributions to the joint IIF/OECD Data Repository Portal.

Blended Finance and Impact Investing:

Using principles and guidelines developed in the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) working with the UNDP, there is an ambition to tap the trillions deployed by major international asset managers, including pension funds, using credit enhancements financed by concessional aid. These voluntary but quality-controlled impact measurements are designed to encourage the creation of portfolios of development projects which are sold on the basis of an ESG label or being Green, Social, Sustainable and Sustainability-linked (GSSS). The challenge here is to develop usable and monitorable definitions and then to construct projects and programmes that can be completed and managed in terms of these quality labels (see references below).

Again, this effort fits with the new development narratives outlined above and with the evolving discussions on MDB reform. If the ambitions of the communities actively promoting these quality labelled bonds were to be realised, this category of development finance would become the major part of developing country debt stocks. The question of how they could be managed in this new Common Framework context has yet to be investigated. Many such assets would already have received official credit enhancements from development agencies so would in principle be able to withstand haircut operations.

National Development Finance Institutions:

An international community of national and regional DFIs has recently been brought together under the Finance in Common Initiative (FICS) launched by President Macron. (FICs 2022) It is supported by a Global DFI Database of some 550 DFIs created and managed at the Peking University, with support from the Agence Francaise de Developpement (AfD). A GDFI website and annual Conferences are devoted to encouraging cooperative endeavours and peer learning to transform the financial system towards climate and sustainability. (GDFI) The next conference is to be hosted by Colombia in the summer. In the new Common Framework context, DFIs may feature as domestic debt is drawn into the equation of haircuts and new lending to support medium term development narratives, although the integrity of domestic financial institutions would be a concern.

Conclusion: Against this complex background of multitudinous new players, institutions and networks, there is a clear impetus toward ambition to capitalize on this transition moment in meeting new global debt-development challenges, it is hoped that the first meeting of the G20 High-Level Roundtable will provide an opportunity for breakthroughs in converging country perspectives and agreement on architectural innovations to provide the world with the capacity to chart pathways forward combining debt workouts with long-term development and financial sustainability.

This paper is the product of the China-West Dialogue based on two CWD Zoom discussions, one of twenty-four participants on January 12, 2023, and a second of twelve participants on January 20, 2023. Based on earlier drafts and these discussions, this CWD draft proposal was written by Richard Carey, with substantive contributions from Colin Bradford. We would like to acknowledge the very significant contributions to this effort by Danny Bradlow, Deborah Brautigam, Homi Kharas, Johannes Linn and Jose Siaba Serrate, among others, while they should not be held accountable for the final content in this version of the paper.

China – West Dialogue: Origins, Principle and Purpose

The China-West Dialogue was founded in April 2018 as a means of bringing together thought leaders from Europe, Canada, China and the United States to pluralize the bilateral US-China relationship. In thirty zoom sessions, more than sixty experienced officials, think tank researchers and academics have now been involved in CWD discussions. A foundational principle of CWD has been that it is with China not about China. China thought leaders are fully involved in shaping the series of exchanges and in participating in all of them.

As a result, CWD is a process which reflects its purpose to achieve results by embracing diversity. Participants are from a variety of professions, disciplines and backgrounds from more than a dozen countries. This results in pluralizing the interactions as a means of generating new perspectives and fresh approaches to the most important geopolitical relationship today. The China-West Dialogue is more a platform than a group. The ideas and proposals in this paper reflect the CWD process, which is designed to bring in a variety of viewpoints in forging innovative ideas and approaches.

Footnotes

1 Kharas and Rivard (2022)

2 Baqir, Diwan and Rodrik (2023)

3 ibid

4 Addis Ababa Action Agenda (2015)

References

Homi Kharas and Charlotte Rivard (2022), “Debt, Creditworthiness, and Climate: A New Development Dilemma”, Washington: Brookings, Global Economy and Development program, Center for Sustainable Development, December, 2022.

LINK: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Debt-creditworthiness-and-climate-1.pdf

Deborah Brautigam (2023), “China and Debt Distress: From Club to Global Governance”, Washington: China-Africa Research Initiative (CARI), slide deck for CWD Zoom Session on January 12, 2023.

Johannes Linn (2022), “Expand multilateral development bank financing but do it the right way”, Washington: Brooking, Global Economy and Development Program, Future Development, November 29, 2022.

LINK: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2022/11/29/expand-multilateral-development-bank-financing-but-do-it-the-right-way/

Fitch Ratings (2022) Understanding Callable Capital

LINK: https://www.fitchratings.com/research/sovereigns/domestic-legislative-processes-pose-risk-to-callable-capital-disbursement-28-11-2022

Daniel D. Bradlow and Magelie L. Masamba (2022), COVID-19 and Sovereign Debt: The Case of SADC, Pretoria: Centre for Human Rights, Pretoria University Law Press, University of Pretoria, 2022.

LINK: https://www.pulp.up.ac.za/catalogue/edited-collections/323-covid-19-and-sovereign-debt-the-case-of-sadc

Masood Ahmed and Hannah Brown (2022), “Fix the Common Framework for Debt Before It is Too Late”, Washington: Center for Global Development, January 2022.

LINK: https://www.cgdev.org/blog/fix-common-framework-debt-it-too-late

Laurence Boone, Joachim Fels, Oscar Jorda, Moritz Schularick and Alan M. Taylor (2022), “Debt: The Eye of the Storm”, London: Centre for Economic Policy Research, International Center for Monetary and Banking Studies, February, 2002.

LINK: https://cepr.org/system/files/publication-files/147590-geneva_24_debt_the_eye_of_the_storm.pdf

Reza Baqir, Ishac Diwan and Dani Rodrik (2023), “A Framework to Evaluate Economic Adjustment-cum-Debt Restructuring Packages”, Paris: Paris School of Economics, CEPREMAP, Finance for Development Lab, Working Paper 2, January 2023.

LINK: https://findevlab.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/FDL_Working-Paper-2_A-Framework-to-Evaluate-Economic-Adjustment-cum-Debt-Restructuring-Packages.pdf

David McNair and Daouda Sembene (2022), “Do Unto Others: Why Today’s Debt Crisis Requires a Different Kind of Thinking”, Washington: Center for Global Development, Blog Post, December 19, 2022.

LINK: https://www.cgdev.org/blog/do-unto-others-why-todays-debt-crisis-requires-different-kind-thinking

China Africa Research Initiative – Loan Data, Debt Issues

LINK: http://www.sais-cari.org/

Lazard Foreign Debt Advisory Group: Getting Sovereign Debt Restructurings out of the Rut in 2023: Three Concrete Proposals. February 2023.

LINK: https://www.lazard.com/perspective/getting-sovereign-debt-restructurings-out-of-the-rut-in-2023-three-concrete-proposals/

Addis Abba Action Agenda (2015)

LINK : https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/2051AAAA_Outcome.pdf

IIF/OECD Data Repository

LINK: https://www.oecd.org/finance/debt-transparency/

OECD Debt Transparency Initiative: Trends challenges and progress (2002)

LINK: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/66b1469d-en.pdf?expires=1676549338&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=CAD067B17B2F6A19FB0EC88AE634C472

DAC Principles on Blended Finance

LINK: https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/blended-finance-principles/

OECD-UNDP Impact Standards for Financing Sustainable Development

LINK: https://sdgfinance.undp.org/sites/default/files/OECD-UNDP%20Impact%20Standards%20for%20Financing%20Sustainable%20Development.pdf

Networks

Finance in Common [FICs] (2022), “Finance in Common Progress Report to G20”, July 2022. See especially the Joint Declaration of All Public Development Banks in the World at the Finance in Common Summit, 12 November 2020, pp. 36-42.

LINK: https://financeincommon.org/sites/default/files/2022-10/FICS%20Progress%20Report%20to%20the%20G20%2C%20July%202022_0.pdf

Network for Greening the Financial System [NGFS] (2023), “NGFS seeks public feedback on climate scenarios”, February 6, 2023.

LINK: https://www.ngfs.net/en/communique-de-presse/ngfs-seeks-public-feedback-climate-scenarios

United Nations Environment Finance Initiative [UNEP-FI]

LINK: https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/green-economy/what-we-do/finance-initiative

Global Development Financing Institutions Database (GDFI), Peking University: 528 Public Development Banks (PBDs) and DFIs.

LINK: http://www.dfidatabase.pku.edu.cn/

World Bank (2022), “Potential Statutory Options to Encourage Private Sector Creditor Participation in the Common Framework”, Washington: 2022.

LINK:https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099802006132239956/pdf/IDU0766c0f2d0f5d0040fe09c9a0bf7fb0e2d858.pdf

OECD (2022), “Making Private Finance Work for the SDGs”, Paris: July 2022.

LINK: https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/blended-finance-principles/Making-private-finance-work-for-the-SDGs.pdf

G20 Italia 2021, “G20 Sustainable Finance Roadmap, Rome: 7 October 2021.

LINK: https://g20sfwg.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/G20-Sustainable-Finance-Roadmap.pdf