It is kinda like wading into a well-developed cornfield; no, maybe it’s more like a cornfield with some incendiary devices strewn throughout. Anyway, this fall the China-West Dialogue (CWD) has waded into a rather concentrated discussion with colleagues and experts around the globe on an examination of Middle Powers (MPs) and their behaviors and policies – Middle Power Diplomacy (MPD).

So, where did we look? We in fact used the fall to showcase a number of possible MPs and to examine the policies and political behaviors of them. At CWD we held the following Zoom sessions:

-

Our lead off was on Japan with Mike Mochizuki (GWU) as the Lead Organizer;

-

then Active Non-Alignment with Latin America, led by Jorge Heine (BU) and former Ambassador for Chile as the Lead Organizer;

-

South Korea with Yul Sohn (Yonsei University) as the the Lead Organizer;

-

Australia and New Zealand with Shiro Armstrong (ANU/EAF) as Lead Organizer assisted by our own Richard Carey (OECD Alumnus); and

-

INDONESIA and ASEAN with Maria Monica Wihardja (ISEAS) as the Lead Organizer.

These were all really terrific sessions with ‘super’ efforts to bring speakers to the sessions who could speak to MP characteristics and describe MPD. Now, these sessions were all held under Chatham House Rules but I have received remarks from some of our speakers and permission to quote these remarks here at this Post.

So, why was the CWD looking at questions of MPD? Certainly, for one, we were examining first which states seemed to qualify as MPs in today’s global order/disorder? Then we were interested in what influence, or potential influence these MPs expressed in the growing global order/disorder – growing tensions between the United States and China and the unremitting regional conflicts in the Middle East and Europe. Where, if anywhere, were MPs influencing international relations and enhancing, perhaps, international stability and advancing global governance actions especially in such critical areas as climate transition, climate finance, debt management, global financial regulation and more? These efforts, we anticipated, could stabilize global relations in the face of current damaging international actions and the sour relations held by the leading powers, China and the US of each other. We were determined to look at MPs especially with the return of a US Trump administration and the possible significant impact of Trump 2.0 on global order stability.

Let me turn in this Post to the remarks of some of our speakers in the Australia and New Zealand session. All the sessions were great but interestingly, two of our speakers in this session described diametrically opposing views of the impact of MPs on the current international order. One was Gareth Evans, a strong proponent for MPs and their influence in international relations. Gareth is rather well known of course. He was an Australian politician, representing the Labor Party in the Senate and House of Representatives from 1978 to 1999. He is probably best known as the Minister for Foreign Affairs, a position he held from 1988 to 1996. Like most inquiries, Gareth starts by trying to define what a MP is. It is not an easy task. As he writes:

For me, there are three things that matter in characterizing middle powers: what we are not, what we are, and the mindset we bring to our international role.

As he then describes it:

‘Middle powers’ are those states which are not economically or militarily big or strong enough to really impose their policy preferences on anyone else, either globally or (for the most part) regionally. We are nonetheless states which are sufficiently capable in terms of our diplomatic resources, sufficiently credible in terms of our record of principled behaviour, and sufficiently motivated to be able to make, individually, a significant impact on international relations in a way that is beyond the reach of small states.

And we are states, I would argue, which generally (although this can wax and wane with changes of domestic government) bring a particular mindset to the conduct of our international relations, viz. one attracted to the use of middle power diplomacy. I would describe ‘middle power diplomacy’, in turn, as having both a characteristic motivation and a characteristic method:

the characteristic motivation is belief in the utility, and necessity, of acting cooperatively with others in addressing international challenges, particularly those global public goods problems which by their nature cannot be solved by any country acting alone, however big and powerful; and

the characteristic diplomatic method is coalition building with ‘like-minded’ – those who, whatever their prevailing value systems, share specific interests and are prepared to work together to do something about them.

Gareth reviews policy initiatives he sees advanced by MPs over the years and described by him as:

Our [MP] impact I think is more likely to be on individual issues, involving what might be called ‘niche diplomacy’, than across the board. But that said, some of those niche roles, as I have just listed. can be of much greater than merely niche importance.

Finally, Gareth sets out what he believes are likely to be possible future initiatives, by at least Australia acting as a MP:

Looking to the future, there are a number of areas in which Australian middle power diplomacy can potentially make a real difference, whether by way of agenda-setting, North-South bridge-building (an aspiration of the MIKTA group within the G20), or simply building critical masses of support for global or regional public goods delivery. These areas include:

– working to make the East Asian Summit become in practice the preeminent regional security and economic dialogue and policy-making body it was designed to be;

– maintaining a leading advocacy role in support of free and open trade, including globally through the WTO and regionally through RCEP and the CPTPP, and vigorously resisting likely protectionist assaults by the Trump administration;

– working to harness, without over-relying on an increasingly erratic US, the collective middle-power energy and capacity of a number of regional states of real regional substance – including India, Japan, Indonesia, South Korea and Vietnam – to visibly push back (through mechanisms like a Quad+, optically useful though not purporting to be a formal military alliance) against potential Chinese overreach in the region;

– at the same time, actively arguing for the US as well as China to step back from the strategic competition brink, and embrace and sustain over time the spirit of détente which, which dramatically thawed relations between the US and Soviet Union: this would involve both sides living cooperatively together, both regionally and globally, respecting each other as equals and neither claiming to be the undisputed top dog;

– building on our longstanding nuclear risk reduction credentials, bridging the gap between those who, on the one hand, will settle only for the kind of absolutism embodied in the Nuclear Ban Treaty, and on the other hand, the nuclear armed states and those sheltering under their protection who want essentially no movement at all on disarmament;

– becoming an acknowledged global leader, not just bit player, in the campaign against global warming, putting our green energy transition money where our mouth is.

It is a MPD projected to counter at least some of the likely erratic behavior of Trump 2.0 international actions.

It is evident that Gareth Evans accepts, in fact promotes, the current and continuing reality of MPs and their capacity to act positively even in a turbulent international setting. This positive MP and MPD view is, as it turns out, in dramatic contrast to another of our Australia speakers, Andrew Carr. Andrew Carr is an Associate Professor at the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, Australian National University. His remarks contrast vividly with those of Gareth Evans. While, as I pointed earlier, Chatham House Rules prevail at CWD, fortunately Andrew and a colleague Jeffrey Robinson of Yonsei University published a recent piece in International Theory, “Is anyone a Middle Power? The case for Historicization”. There Andrew and his colleague lay out their view of MPs and MPD:

We find that while there is some variation, middle power theory can no longer help us distinguish or interpret these states. As such, we conclude the middle power concept should be historicized.

In blunt terms, the middle power concept does not capture anything substantive about the behaviour of mid-sized states. It should therefore not be used by scholars any further.

Andrew sees the concept as historically grounded and no longer sustains relevance and in his view must be assigned to a historical period of international relations. The two experts make it clear that using MP and MPD has outlasted its usefulness.

This is a rather clear statement and probably needs some further explanation. Now, interestingly the two researchers examine six MPs – the traditional MPs, Australia and Canada but as well newly emerging MPs – Indonesia, Turkey, South Korea and Mexico. Now Carr and his colleague suggest that there are 30 MPs but their analysis relies on the six just identified. They come away, however, suggesting this:

Argument 1: the middle power concept is unable to shed its 20th century historical legacy

Argument 2: contemporary states no longer reflect the core theoreticalpropositions of the middle power concept

There is much insight from the analysis of these two experts. Yet the bottom line is clear:

The evidence from our six case studies is not universal, but clear trend lines and patterns can be observed. As the 21st century has worn on, these states have all been less internationally focused, less supportive and active in multilateral forums, and shown sparse evidence of being ‘good citizens’.

Put another way the changing international structure is reshaping the behavior of MPs:

As international structures change so too will the power, status, and actions of non-great power states. The changes occurring today are removing the foundations upon which the middle power concept was explicitly created, as supporters and legitimizers of the US-led liberal international order.

So, where does that leave us in understanding which states are the MPs and what can we expect from MPs? Is there a MPD? Does such MPD correspond to what Gareth Evans describes; or are we in a global order today where such MPD can only be seen ‘in the rear view’ as Andrew Carr explains with his colleague Jeffrey Robertson?

Well, this is only the beginning of an answer but it is useful to look to a recent piece by Dr. Dino Patti Djalal. Now, Dr. Djalal is the founder and chair of the Foreign Policy Community of Indonesia (FPCI) and chair of the Middle Power Studies Network (MPSN). In November Dr. Djalal published Middle Power Insights: 1st Edition. What is immediately evident is the membership of MPs in this Report was somewhat distinct from previous authors, at least from Gareth Evans.

Like others, of course Djalal attempts to identify the current universe of MPs and what policies they promote. As Djalal describes:

In this article, I refer to middle powers as countries that, by virtue of their considerable size (population and geography), weight (economic, diplomatic, and military strength), and ambition, are placed between the small power and great power categories.

While the objective measures, size and weight are fairly well described, ‘ambition’ is not so easily determined. With these features Djalal suggests:

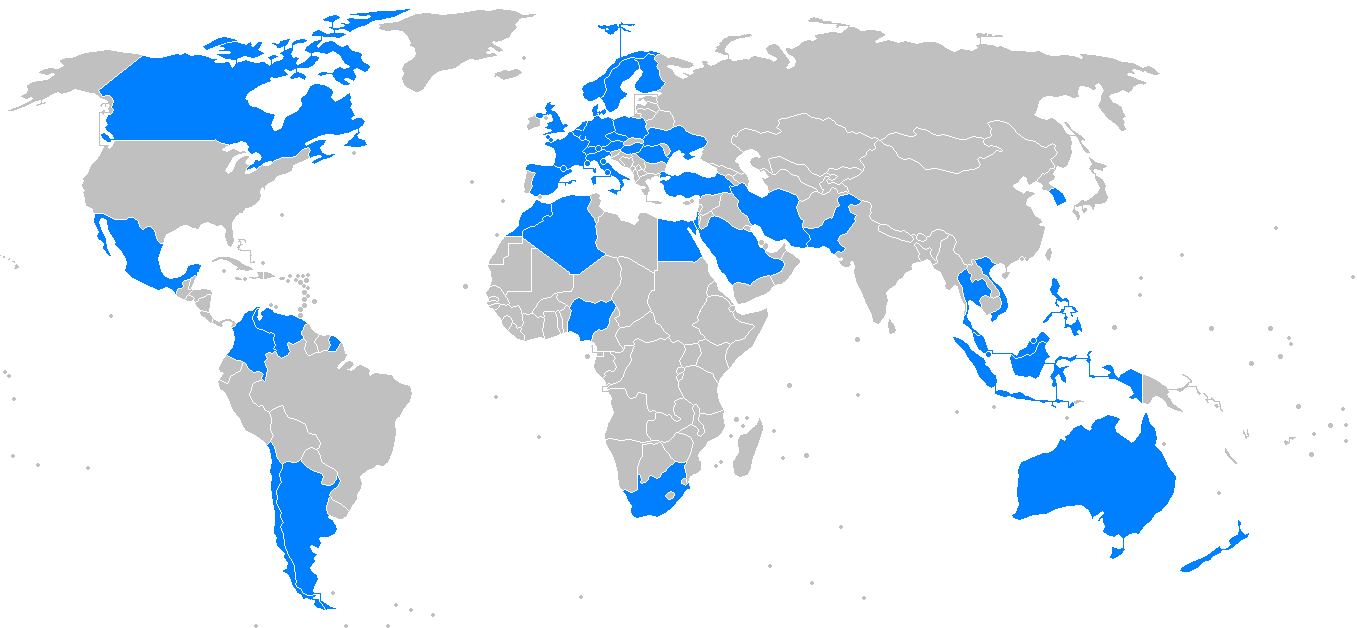

Of the 193 countries in the world today, around two dozen qualify as middle powers – some are in the Global North but the majority are in the Global South.

Here, then, is an emerging shift in today’s MPs. We are looking at MPs many of whom today are in the Global South and their behavior is also shifting:

While all of the middle powers of the North are committed to military pacts, most middle powers in the Global South are non-aligned and tend to pursue strategic hedging. In fact, while the middle powers of the North have developed a fixed view against China, those in the Global South (except India and South Korea) tend to have an open mind and are keen to explore closer relations with China.

Unlike those in the North, middle powers of the South are also generally more averse in using sanctions as an instrument of foreign policy.

It also matters that the Middle Powers of the Global South, relative to those of the Global North, are generally strong proponents of “non-interference” and are more sensitive about the principle of “equality”.

So their policy behavior is less intrusive and by implication less committed to global policy. It would seem to suggest that many of today’s MPs target their actions at the region. As Djalal describes:

More and more, middle powers are positioning themselves to be a driving force in shaping regional architecture, thus compelling them to step up their response to the challenges inherent in their neighborhood. They are also spearheading various minilateral initiatives that can potentially supplement the provision of global public goods and also enhance the space for meaningful dialogue.

By constantly resorting to strategic hedging and diversifying their strategic relationships, middle powers can render multipolarity less volatile and more stable.

At a minimum, then, according to Djalal, the new Global South MPs exercise their MPD at the regional level and possibly in small groups, minilaterally, at the international level. More clearly needs to be examined here.

So, today was a start but just a start. Much more will need to be examined. We will return to today’s Middle Powers and their Middle Power Diplomacy, especially as the Trump administration unveils its foreign policy actions.